Some promising A2J news from the Hoosier state.

Folks, this update requires a bit of context.

As regular LE readers know, back in 2022, the content of Legal Evolution began to shift as I wrote a series of essays seeking out the root causes of our present-day social, political, and economic strife. See Posts 312 (original Gilded Age lawyers), 319 (US policies leading to wealth inequality and the “End of History” illusion), 321 (empirically based theories of national decline). As a law professor who teaches the ABA-required legal ethics course, I found this subject matter impossible to avoid. Cf. ABA Preamble ¶ 6 (“[A] lawyer should cultivate knowledge of the law beyond its use for clients [and use it to] … further the public’s understanding of and confidence in the rule of law … because legal institutions in a constitutional democracy depend on popular participation and support to maintain their authority.”).

In January 2023, I shut down Legal Evolution because I was no longer convinced that legal innovation per se was the best use of my time. See Post 349 (framing this dilemma as the Mindshare Matrix). In January 2024, I stated that when LE resumed, it would have fewer posts and more PeopleLaw content, as I was focusing most of my time on promising A2J topics in Indiana. See Post 350 (discussing conclusions from a long period of discernment).

The key point of this update is that, for the past three years, I have been immersed in applied research (see Post 001 definition), which has required immense trench work. But alas, there comes a day when it’s time to write. This post outlines how the Indiana Supreme Court has changed the regulatory structure is significant ways and how these changes could lead to major A2J gains for low- and moderate-income Hoosiers. Furthermore, if it works, it will also be a major workforce development initiative that should eventually touch all 92 Indiana counties.

For a comprehensive look at my work over the last three years, see this forthcoming research note, Henderson & Raymond, “Indiana Supreme Court Uses Applied Research Practicum at Indiana University to Gather Facts for Reform Efforts,” 100 Ind. L. J. __ (forthcoming 2026) [hereafter ILJ Research Note]. Otherwise, this post hit the highlights.

Indiana Supreme Court acknowledges the problem, takes action

In the April 2024 order establishing the Commission on Indiana’s Legal Future, Chief Justice Loretta Rush acknowledged a “critical shortage of attorneys,” with the problem being “especially acute in Indiana’s rural and most socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, as well as the public service sector.” Order Establishing the Comm’n. on Ind.’s Legal Future, Cause No. 24S-MS-116 (Apr. 4, 2024). The purpose of the Commission was to explore options to address the attorney shortage and to present its findings and recommendations to the Court for future action.

I was fortunate to be one of the attorneys who got the call to join the Commission. During the previous year, I was active on the Court’s Innovation Committee. During this period, I got the sense that the Court’s Office of Judicial Administration had the mindset and the personnel to design and implement important change. Thus, I was glad to be on the bus.

The Commission’s Interim Report, issued in July 2024, reiterated the importance of solving Indiana’s attorney shortage but also concluded that addressing the shortage “will require opening doors of legal representation to individuals beyond lawyers.” Comm’n on Ind’s Legal Future, Interim Recommendations (July 30, 2024) at 7. The Commission defined this new category of worker as “allied legal professionals” (ALPs). Id at 8 (acknowledging that ALP was the term used by the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System, IAALS).

Among the Commission’s many findings and conclusions was a recommendation that the Court provide “startup funding to law firms using a nonprofit business model,” which the Commission suggested could be “coupled with the future availability of allied legal professionals” to provide legal services to the broad swath of low- and modest-income Hoosiers who struggle to afford a lawyer. The Commission noted that with modest investment, such a model may become a “long-term, self-sustaining endeavor.” Id 10-11.

In early October 2024, the Indiana Supreme Court accepted the majority of the Commission’s recommendations, including those regarding ALPs and the nonprofit law firm model, and directed the Court’s Innovation Committee to develop parameters for implementation. See Order on Interim Recommendations Made by the Comm’n. on Ind.’s Legal Futures, Cause No. 24S-MS-116 (Oct. 3, 2024). In March 2025, the Court accepted these parameters, thus creating a regulatory pathway to build this new type of law firm. See Initial parameters for the Innovation Comm. Regulatory Pilot Program (Feb 26, 2025) (adopted by Court in March).

In very practical terms, what is the significance of these changes? Collectively, the Court’s orders create a pathway for, among other innovations, a new law firm model that can fully leverage the time-saving advantages of AI and related technologies while retaining the necessary human touch provided by allied legal professionals and lawyers. This new model is nonprofit + allied legal professionals + technology, which has the potential to scale to the whole state (the model, not necessarily the entity).

Who will build it?

Changing rules (or, more precisely, relaxing prohibitions) is not the same as building the infrastructure necessary to deliver a new service or solution. Cf. Post 140 (discussing the difference between “rule makers” and “risk takers”). The latter requires time, expertise, careful planning, and capital.

Over the last several decades in the United States, we become increasingly reluctant to fund public works, instead embracing an ideology that favors private markets. But can A2J realistically be solved by the PE/VC crowd? After two decades in the legal innovation trenches, I’ve grown increasingly skeptical.

In my work with the Commission for Indiana’s Legal Future, I argued that we should explore the viability of a nonprofit law firm model focused on high-volume, low-complexity legal work delivered at an affordable per-unit cost. If delivered at scale, the nonprofit could be a self-sustaining operating business. Further, I said that if the Court created a pathway to pilot a new nonprofit business model that could employ allied legal professionals to provide limited scope legal services, I would do everything in my power to build it. Cf. Post 059 (discussing how the original legal storefront revolution of the 1970s and 80s failed because lawyers hated the repetitive nature of the work, yet their legal assistants and secretaries loved it).

In the three years that LE was substantially dormant, I worked on this project in the hope that it might actually go forward. This work has resulted in two interconnected initiatives directed toward the same goal: [1] the Applied Research Practicum (ARP), an ongoing course at Indiana University that engages undergraduate and law students to build foundational infrastructure for [2] a Nonprofit Law Firm operating business that focuses on low-complexity, high-volume legal services for low- and moderate-income Hoosiers.

Below is a brief description of both.

The Applied Research Practicum (ARP)

As the Committee on Indiana’s Legal Futures was taking shape, I worked with Professor Angie Raymond, Chair of the Business Law Department at the Kelley School of Business and long-time contributor to the Court’s innovation efforts, to organize an applied research course in which we could use undergraduate and law students to gather facts for the Court’s A2J efforts. But for Angie and her skill at finding ways to enable multiple academic units to collaborate, including securing pockets of funding, the ARP would never have gotten off the ground.

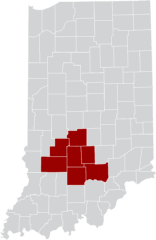

During the first year of the course (2024-25 academic year), the ARP completed a comprehensive stakeholder analysis of the seven-county area surrounding Indiana University. Drawing upon detailed interviews, focus groups, and courtroom observations conducted by a small army of students, the study found that Indiana’s attorney shortage is significant—virtually all lawyers in the seven-county area were swamped with work and struggled to recruit entry-level lawyers and professional staff. Yet these same overworked lawyers reported turning away a large volume of work because the low-value cases could not support their fees. In brief, the attorney shortage and access to affordable legal advice are separate issues with only partial overlap. Building on the pathway created by the Indiana Supreme Court, the study concluded that the next iteration of the APR would focus on developing the necessary infrastructure for a pilot nonprofit law firm that employs the first generation of Indiana ALPs, as this appeared to be the best way to reach this large latent legal market. For our full results, see ILJ Research Note, supra.

During the second year of the course (2025-26), which we are now halfway through, our students, with the help of numerous guest instructors eager to help the A2J cause are process mapping areas of high need (family law, debt collection, consumer bankruptcy), gathering requirements for a technology platform (expert system, guided interviews, workflow, doc automation, gen AI), and partnering with a local family law court to build an on-site help center, thus enabling the ARP to work backwards from the needs of pro se litigants. See Spring 2026 APR Syllabus.

The most valuable insight I have learned from this experience is that the classroom combined with fieldwork is the ideal vehicle for undertaking difficult, first-of-its-kind applied research. Although some of the work is mundane for experienced researchers, it’s foundational learning for junior team members. Conversely, the best antidote for an entrenched problem is often the fresh eyes of an undergraduate, as lawyers and even law students get socialized into the old way of doing things. Over the first two years, we’ve also recruited a handful of students who have stayed with the project because they see the nonprofit law firm as a potential career path worth their time.

There is no shortage of difficult, first-of-its-kind work to be done. The projects for next year are already piling up. Our long-term vision is for the ARP to become a profoundly cost-effective way for Indiana University to return value to the state.

One more note of thanks: Robert Rath, the Court’s Chief Innovation Officer, championed the ARP, secured a modest annual budget for us, and frequently visited our class. As we frequently told our students, “Bob is our client.”

Pilot Nonprofit Law Firm

The purpose of the ARP is build foundational infrastructure — at a higher level of quality and at a lower overall cost — for a pilot nonprofit law firm that combines a necessary human touch with low cost, efficiency, and scale. This entity will be an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit that will operate under the Indiana Supreme Court’s regulatory pilot framework. See Initial Parameters.

This nonprofit firm differs from traditional legal aid in three ways:

- Earned-revenue focus: Like hospitals and universities, the firm becomes a self-sustaining operating company.

- Legal operations discipline: Services are standardized, with a focus on volume, client experience, and low per-unit cost. Thus, the operating board and management team will have a legal ops mindset.

- Allied legal professionals: Under Supreme Court rules, ALPs will deliver low-complexity services under the supervision of a lawyer, thus enabling our lawyers to practice at the top of their license.

The nonprofit firm will initially serve the same seven-county region studied in the Year 1 ARP stakeholder analysis. This enables us to leverage relationships in a well-understood legal ecosystem. I cannot overstate the value of that seven-county stakeholder analysis, which is fully documented in the ILJ Research Note. As the model improves, the ARP and its alumni will help it scale to other parts of the state.

Before we launch, we hope to have three years of funding in place, which will enable us to focus on improving the overall business model. Thus, all operating revenues will be placed in reserves for the day we have to prove we’ve become self-sustaining. Because the emphasis is on the business model and its scalability rather than this specific nonprofit law firm, all know-how and tools will be shared with the Indiana A2J community. If the model is widely replicated throughout Indiana, we can safely say we achieved our mission.

More updates to follow. wdh.